It has been almost sixty years since the fluoridation of our nation's drinking water became national policy, and almost as long since fluoridation was a major controversy, sparking post nuclear paranoia in swaths of the populace. Today it is a commonplace fact that our water has fluoride in it and the benefit to our dental health is common record (with some conspiracy theories still raging). But how is fluoride added to the water supply? I asked that question of Dick Barnes of the U. S. Department of Fluoride, and he invited me to visit a fluoride processing site in upstate New York.

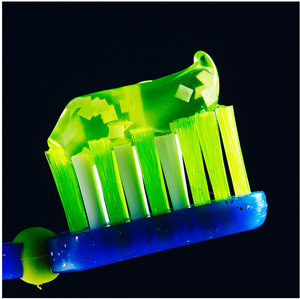

It has been almost sixty years since the fluoridation of our nation's drinking water became national policy, and almost as long since fluoridation was a major controversy, sparking post nuclear paranoia in swaths of the populace. Today it is a commonplace fact that our water has fluoride in it and the benefit to our dental health is common record (with some conspiracy theories still raging). But how is fluoride added to the water supply? I asked that question of Dick Barnes of the U. S. Department of Fluoride, and he invited me to visit a fluoride processing site in upstate New York.I shot upstate and met Mr. Barnes at the Croton reservoir. We hiked to an adjacent reservoir where a number of workers were busy tipping bins of used toothpaste tubes into the water.

"Yes, we used to use chemical fluoride, measured in parts per million, with a carefully regulated lab to introduce the fluoride," said Mr. Barnes, "but in the early seventies we switched over. People had other concerns with the war in Vietnam, and the fluoridation process got deregulated about the time when we started some innovative efficiency planning. It was determined that the military and other government organizations rationed millions of tubes of toothpaste a year. We found we could kill two birds with one stone, by depositing them here."

In an organic process the dilution of these toothpaste dumps adds fluoride to our drinking water, while creating biomes unlike any seen in the history of Biology. Calcium phosphates and silica abrasives from the paste have formed a layer of silt on the bottom of the pond. Freshwater crabs have taken to using the tubes for protective shells. They've grown long thin, spindly legs to protrude from the narrow openings of the tubes.

"Every first Thursday we have a crab steaming dinner at the processing center," said Cliff Nomans, one of the toothpaste dumpers, "There's not a lot of meat in the legs, but you can suck out the juices, and it has a clean minty taste, and then you can squeeze crab meat out of the tube. The trick is to squeeze from the bottom."

Another layer of sediment includes the gels layering from bright green to blue to red, creating a translucent blob on the floor of this man made lake. "We always joke that there should be jellyfish here," laughed Mr. Noman.

What they do get is frogs. Translucent, striped frogs. Only there's no steaming or barbecuing these frogs every first Thursday; these frogs are highly poisonous. Many have six legs, but Mr. Barnes assured me that has to do with the mysterious affliction plaguing frogs all over the world, and not specific to this reservoir. There is a breed of stork that has evolved a resistance to the frog toxin, the only side effect being that they glow in the dark.

Said Mr. Noman, "I don't know how crocodiles got up here, but they're thriving. We don't know if they're eating the storks or the frogs or both, all I know is you've got to watch out for those jelly crocs, because they're see-through too."

The detergents in the toothpaste causes foamy lather lines along the shore of this lake. This has created a new home several breeds of insects have adapted to. Mosquito larvae and water striders live inside the bubbles. Spiders have developed varying techniques to harvesting in the foam.

Professor Leman Frears studies these creatures. Said Frears, "Some of the spiders have become hunters." He showed me a tiny spider pursuing a wintergreen gnat. The two bugs scrambled slowly as they fought the minisci of the bubbles. They penetrated a succession of bubbles, until finally the spider got into the same bubble as the gnat, and fed. Some spiders still hunt the old fashioned way. Frears showed me the strange designs of spider webs in the froth.

"They harvest these webs at the plant." said Frears, "If you ever use flavored dental floss, some of that is spider web."

How far does the effect of this fluoride processing site go into the environment? Frears said the full effects, while probably benign, were unknown. "All I know," said Frears, "Is that the local bats have forgone sonar, relying more of taste. They fly with elongated tongues, sensing the mint, cinnamon and wintergreen flavors that indicates an insect is nearby."

I was amazed by what I saw at the fluoride processing site. As we hiked back to our cars from the reservoir, Dick Barnes and I heard a loud sound in the woods. We went to investigate. I only caught a glimpse of the creature, but it was large, and it was like nothing I had ever seen. I can't adequately describe its features. I don't know if I saw fur or foam, arms or tentacles. But it smelled like mint.

--Dan Kilian

The Polar Turtle

sKwirrels